Deep Analysis 1 - Proteus

Welcome back to my humble blog! This is a continuation of my original post on analyzing the malware strain known as Proteus. I recommend checking out my first post on Proteus where I perform some basic static and dynamic analysis: https://wakester25.github.io/Proteus-Analysis/. In this entry I plan to pick up where I left off in the last post and begin performing some deep static analysis. Due to the in-depth nature of deep static analysis I will be breaking this up into multiple posts. I have to say up front that I am still learning reverse engineering as I go and that deep analysis is completely new territory for me. In diving into Proteus I have faced some of my toughest challenges yet but at the same time it has been a super rewarding experience!

So if we recall my last post we left off with running the malware in a VM to see what functionality it performed. In doing so we were able to extract the following IOCs:

- proteus-network[.]ml

- 49FD4020BF4D7BD23956EA892E6860E9

- DW20.EXE

- gchrome.exe

- C:\Users\admin\Documents\New text document.txt

- C:\Users\admin\AppData\Roaming\Tamir.SharpSsh.dll

- C:Program Files\Common Files\Microsoft Shared\DW\

- HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run, value=C:\Users\admin\AppData\Roaming\chrome.exe

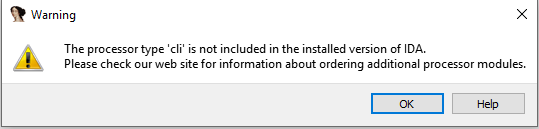

While these IOCs prove useful as a detection mechanism we still have gained very little insight into the actual functionality of the malware. To learn more about how the malware operates we will be digging in and attempting to disassemble the executable. For those who don’t know, disassembly is the process of taking an executable and getting back code that can then be analyzed. When code is initially compiled it is turned into instructions that can be executed by the processor. Disassembly is the art of taking these instructions and representing them at a higher level assembly language that is considered more human readable. The tool of choice to do this is IDA Pro, which will take a passed executable, disassemble it and present us with the ASM code. However, in passing gchrome.exe into IDA I actually hit my first hurdle. In attempting to open the executable in IDA I kept receiving errors about “processor type cli not included”.

ghcrome.exe IDA Import Error

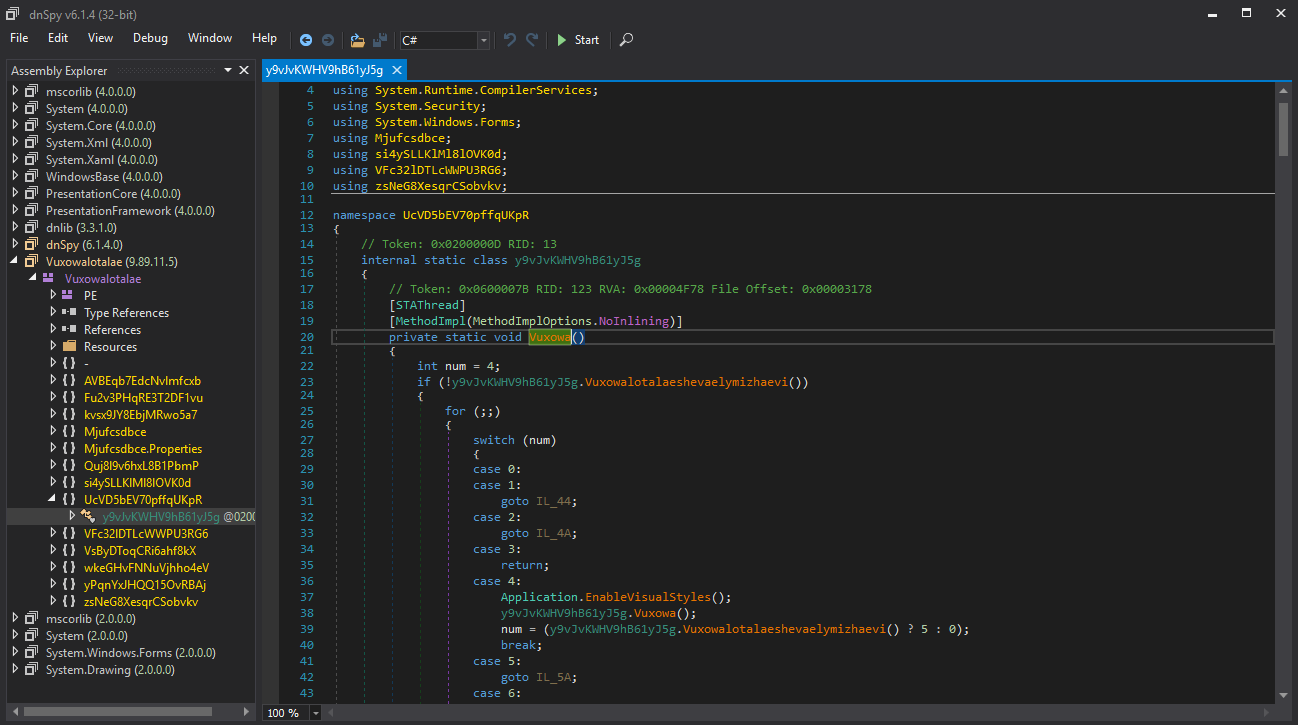

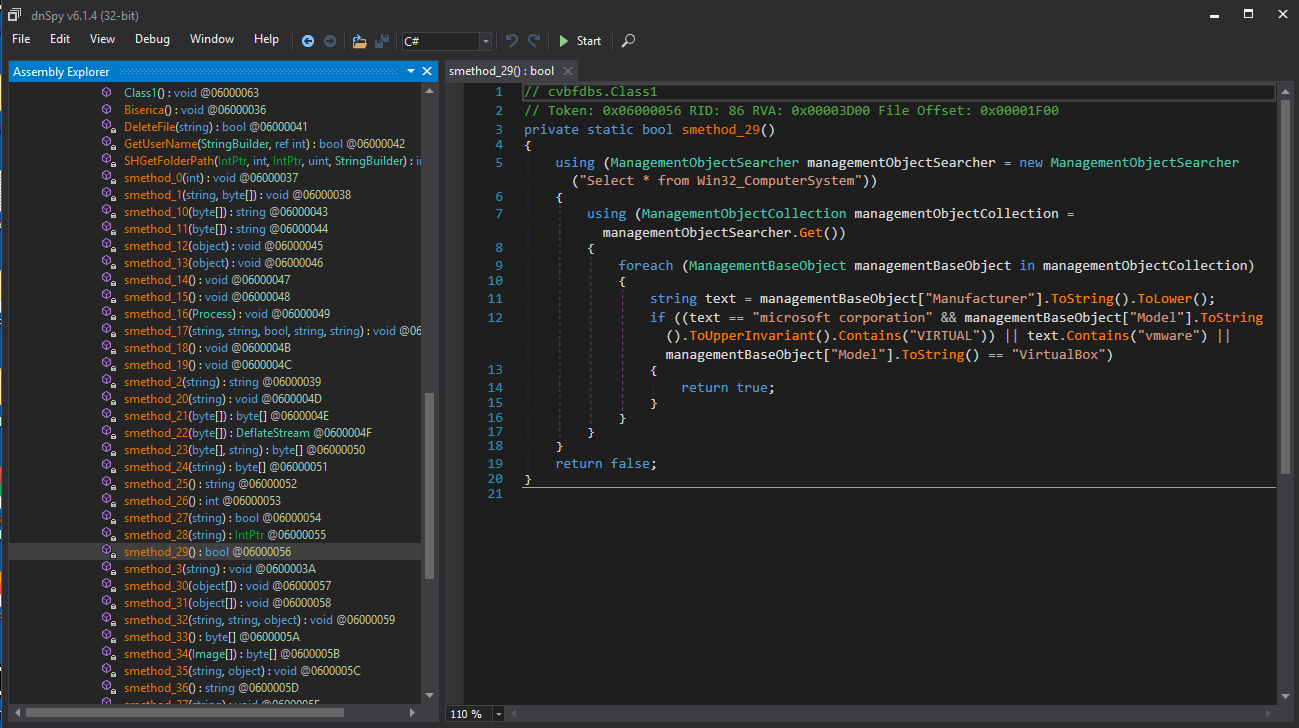

This was really confusing to me as I had assumed this assembly was crafted for the x86 processor type? Well, long story short I wasn’t wrong, but I had assumed some incorrect things about the executable. If we remember from my last post we had discovered gchrome.exe was a .NET / C# application, which is a programming framework I have little experience with. After multiple tutorials on .NET / C#, I learned that while .NET applications may seem like a normal PE executable, it is actually a representation of something known as an “intermediate language”. The short and dirty explanation is that .NET uses a just in time compilation architecture, which means that code is transformed into an “intermediate language” which is then further compiled at run time. This means that we can’t use typical disassembly tactics used for normal x86 executables and instead have to use methods specific to .NET. The good news is this intermediate language is consistent and we can rather easily get something back that closely resembles the original source code. Cool right! To actually solve this problem and disassemble the application I ended up using a tool known as dnSpy. dnSpy is pretty much a disassembler and debugger that was built specifically for .NET applications. Using this I was able to get back extracted C# classes / namespaces from the application. In doing this however I found that all the code was heavily obfuscated.

Extracted Obfuscated Code

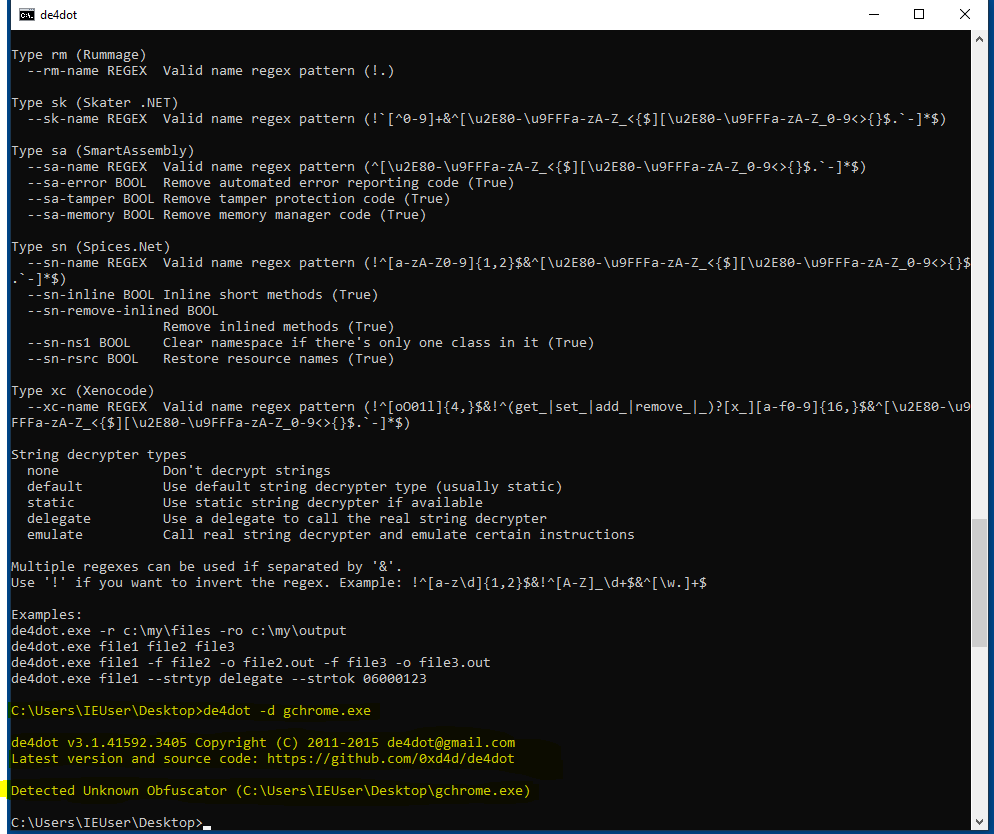

In my first attempt at bypassing this obfuscation was to try and manually step through the code to see if I could decode what was going on. I quickly learned that due to the amount of code and obfuscation this was not going to be possible. I then turned to my trusty friend google and learned that .NET / C# obfuscation are commonly used techniques and there a number of tools to both obfuscate / deobfuscate .NET such as de4dot. After multiple attempts, none of the tools I tried were able to detect the obfuscator being used.

De4dot unable to detect obfuscation

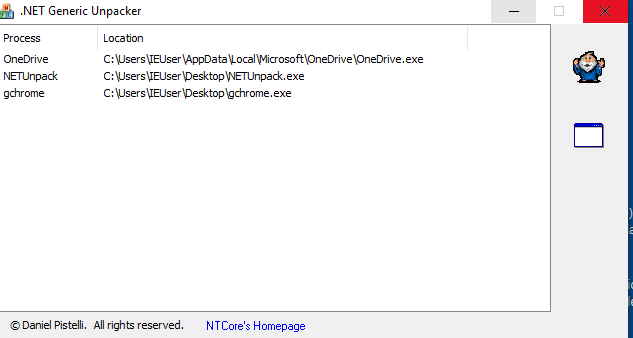

At this point a few weeks had passed and I was about to just toss in the towel when I stumbled upon another technique for unpacking code, dumping from memory. Conveniently one of the developers of IDA, Erik Pistelli, actually created a tool to do this known as .NET Generic Unpacker. How this works is the unpacker program waits for the obfuscated wrapper application to decrypt the source .NET code and extract it leaving you with the source MISL code. From here you can then use dnSpy or dotPeek to disassemble it into the true unobfuscated C# code.

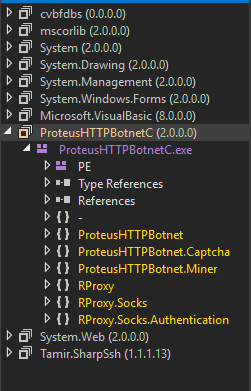

After running the malware on my VM and using .NET Generic Unpacker, multiple DLL / EXE files were extracted. Tossing these files into dnSpy I was able to find that the malware was actually composed of three .NET components:

- ProtuesHTTPBotnetC.exe

- Tamir.SharSsh.dll

- cvbfdbs.dll

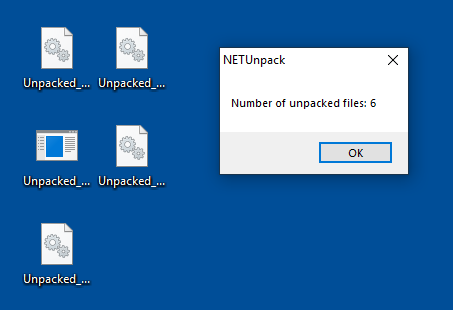

.NET Generic Unpacker and the unpacked files

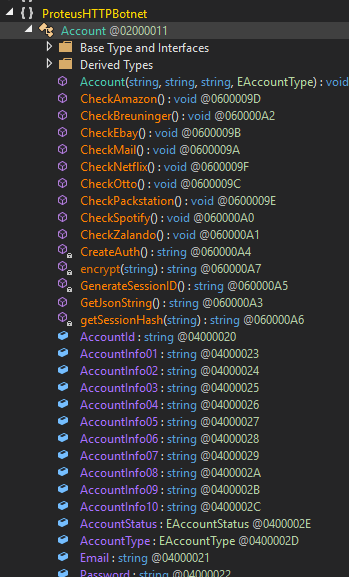

Both ProtuesHTTPBotnetC.exe and Tamir.SharSsh.dll seemed to be unobfuscated and resembled the original source code while cvbfdbs.dll still seems to be further obfuscated. Glossing over the files I was able to find functions for CryptoMining, Connection Proxying and even a function that tests harvested accounts against a number of services (Amazon, Netflix, ect).

Disassembled code / The account checker function

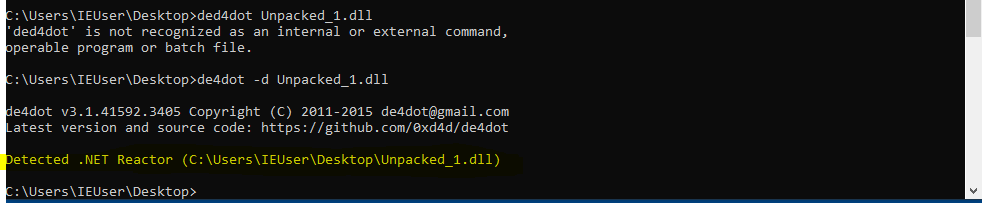

I also decided to just try and toss cvbfdbs.dll into de4dot and was actually able to decrypt it as it was packed using .NET reactor. Looking over that code quickly it seems that it actually houses a number of functions for anti-debugging / assembly.

Detecting .NET Reactor and Anti-Debugging Function

But more on that later. As I am still working on going through each of these files and I want to get this post up I am going to take a pause here. I have to say, while I realize I still am only scratching the surface of malware analysis / reverse engineering, this post has been the most rewarding to create. The feeling of finally overcoming a problem with real malware after hours of failures is a high within itself. This has made me super excited to continue pursuing and learning about malware analysis. Also, during this analysis I learned a lot about obfuscation techniques but still have some questions I need to get answered. For instance, while I used the .NET Generic Unpacker tool to dump the source code from memory, I would like to know how it is actually able to do this. I am not a fan of using a tool blindly without at least understanding how it does what it does. But for now I still need to still finish up analyzing Proteus and its many functions.

Tools Used:

- dnSpy / dotPeek : .NET disassembly / debugging

- IDA Pro : General PE disassembly

- De4dot / .NET Generic Unpacker : .NET deobfuscation